N.T. Wright is among the two or three most influential theologians alive today. And recently, I had the privilege of spending some time with him.

5 Ways to Help Refugees Right Now

There's a lot of chatter on social media about President Trump's executive action. So, in an effort to turn passion into Kingdom action, I humbly submit for your consideration five steps we can take right now to be helpful toward this cause:

Donate

A lot of great, godly charities are funneling money and resources to those fleeing persecution. Because we live in the richest country on earth, our donations can make a huge impact. Consider partnering with them. Here's one, and here's another, and here's another one.

Pray

If you belong to Jesus, you have at your disposal the most powerful, history-altering resource known to humanity — prayer. Pray for the refugees. Pray for the leaders of their broken countries. Pray for our own leaders, to practice compassion for the least of these while trying to secure our borders. Pray against a spirit of fear which foments our worst natures.

Volunteer

There are some great organizations that serve incoming refugees. Let's be known as those who welcome them, care for them, and serve them. We Christians are pro-life people. From conception to resurrection, people matter to God. Let's find ways to serve them.

Invite

After preaching yesterday on the refugee crisis and God's heart for the nations, I spoke with many internationals who were grateful to have found a place that welcomed them. While I know a thousand things our church can do better, I was glad for the little grace of foreigners feeling welcomed in our midst. When you meet your refugee neighbor, invite them into your community, your home, and your circle of friends, and yes, your church.

Advocate

Part of the responsibility of God's people is to speak prophetically to our leaders when they go astray. Protest is a longstanding American tradition and a protected civil liberty. So, when appropriate, be present to be heard. Call your congressmen and senator. Advocate for godly, compassionate, and wise rule in our land. Just remember that as you do, God hears what you say and how you say it. In these gatherings there will always be temptation to give way to the worst parts of our common humanity. So often our enemy can turn righteous anger into sinful rage. So, as a mentor once told me, speak truth in a way that you'd want to hear it if you were the one in the wrong.

You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind, and your neighbor as yourself. (Lk. 10:27)

I therefore, a prisoner for the Lord, urge you to walk in a manner worthy of the calling to which you have been called, with all humility and gentleness, with patience, bearing with one another in love, eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace. (Eph. 4:2-3)

Of Discipleship and Destiny

It was a fresh, autumn day. "Fresh" is that euphemism that Scots use to describe utterly terrible, grey, rainy weather that most other places in the world would deride. Call it a coping mechanism.

Anyway, it was fresh with a bit of sun that day.

I just moved to Edinburgh with my wife, our three-month-old daughter, our dog, and her grand piano. I was 21, she was 22, and we'd been in country for a few weeks. All our earthly possessions had been delayed, not to arrive for another couple of months. But, it was time to get to work.

We'd moved to help a team of men and women plant a new church in the city, and the work couldn't wait for my couch to arrive. So, off to the train station I went to get to Edinburgh Uni. My job was to reach out to incoming freshmen (or freshers, as they're known there. Boy, they love that word "fresh,"...) I arrived to Teviot Square. I was to tell students about Jesus. This was the moment I'd prayed for, worked for, hoped for, and raised a small pile of money for. It had all come to this. I stepped into the square, teeming with students.

I was terrified.

I probably walked around that square for an hour, praying and asking God to open a door, to give me courage — to make it easier. Then, I spotted a Georgia Tech hat.

As a graduate of FSU, I knew what that meant. I'd found a southerner — a dude who rooted for an ACC school, no less. This was my man, so I approached him. "Are you from Georgia?" I asked this dude. Confused, he tilted his head and replied, "no."

As it turned out, this fellow had gotten the hat from his roommate, who was (and is) American. He borrowed it and stepped out to play a bit of frisbee there in the square. We struck up a conversation. He attended an outreach we were sponsoring. He and I began to get together for coffee. I told him about Jesus, and about the destiny and calling on his life. After a while, he began to believe me.

Weeks later, this young man found his way to the first few worship gatherings of our newly formed church — Every Nation Edinburgh — meeting weekly at the Dominion Cinemas. He joined our setup team. Then our worship team. This young Scot became one of the first men I had the privilege of discipling. By the end of his first year at University, God had done quite a work in his life.

For the five years that we lived in Scotland, I enjoyed this relationship with Gordon. I was mentoring him in the faith, and in a bit of life, too. I played music with him (since I was the worship leader), and I did a bit of campus ministry with him (since I was the campus minister, too). I got to watch a teenage boy who wandered to university become a man of God stepping into his destiny.

Seven years ago, I said goodbye to Gordon, to Scotland, and to many other young men into whom I had the privilege of investing a bit of my life. Hope and I packed our bags, a few more kids, and her grand piano, and moved home.

This week, I got to return.

The occasion was to be one of the many men who witnessed Gordon become the Lead Pastor of our church in Edinburgh. The dream of any missionary is to hand the work over to locals, and for the many of us who invested our lives into this place, it was a glorious occasion of thanksgiving to see this young man and his amazing wife step into leadership. Missionary dream come true.

I had the chance to catch up with many old friends this week, pray with many, encourage many. Now that I'm on my way home to Boston again, I can't help but draw a few conclusions.

Discipleship is About Destiny

Twelve years ago I could have never known that Gordon would become a pastor. That's not why I spent time with him. I invested my life and faith into this young man because Jesus calls his disciples to make disciples. The fun part, only known to the Lord at the time, is the result. I'm convinced, however, that if we'll stick by our calling to make disciples we will never cease to be stunned at the destinies that are walked into.

Discipleship is Not Automatic

I'm tempted to make discipleship a class or a program. And, while classes and programs are indispensable, discipleship ends up being about relationships. Those don't just happen. They aren't automatic. They require a high degree of intentionality.

Destiny is Up to God

We don't make disciples because we see their destinies. We never know what will happen, only God does. I think it's safer that way. God wants us to be faithful to invest in others. We embody faith in the gospel and trust in the God of the gospel when we leave the results to him.

I'm proud of Gordon. I'm grateful to God. And, I'm really humbled and stunned that this is the kind of work I get to do. By grace, it's work that, for me, will never stop.

Can a Christian Be Patriotic?

I remember the little church we would frequent had two flags: one American, one Christian. One Fourth of July weekend, I clearly remember singing the National Anthem and the Battle Hymn of the Republic. Church and State were partners in those days, and the patriotism seemed to go hand-in-hand with Christianity. And, in many churches today, this is still the case. But should it be? Some Christians believe quite strongly that we cannot be patriotic. With our citizenship in Heaven (Phil. 3:20) shouldn't be skip the fireworks on the Fourth and instead long for the country that is coming — the one without corruption, without injustice. The one ruled by the One great King?

Not Blind Patriotism

Both of these views are right, and both are wrong. Blind patriotism is clearly wrong. And, many American Christians are blindly patriotic. Believing only in the Christian America origins of our nation, this view utterly ignores the weeds of injustice which have grown up along the good stalk of the puritanical vision. The same weeds that today seem to be choking it out altogether in many quarters. Indeed, our citizenship is in Heaven, so we can never be blindly patriotic.

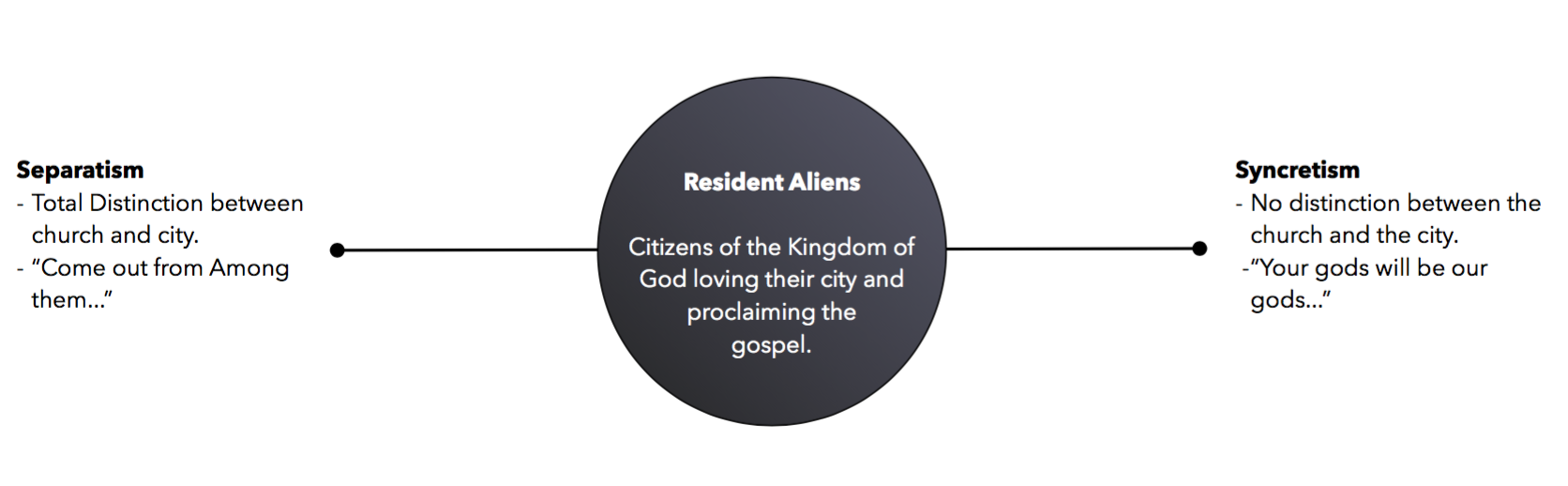

Worst of all, though, blind patriotism always devolves into a kind of syncretism. It muddies the clear, fresh water of the gospel, trading it for the mixed, brackish, and unhealthy false gospel of "America first."

Not Separate Kingdoms

So why not separate entirely? Why would Christians even bother engaging in an American that is wrought with so many problems? Well, the simple answer is, the Bible commands us to engage the world, not retreat from it. While we're not of it, we're still in it. (Jn 17:16) The very reason that God's people remain in the world is to engage it with the gospel, so that every nation might be present before God in worship for all time. (Rev 7:9)

Tragically, those who advocate the church as a completely different kingdom than the world devolve into a sub-Christian separatism. I'm just glad Jesus wasn't a separatist.

Patriotism as Resident Aliens

The Apostle Peter gives insight into this question in his epistle. He calls the church, “elect exiles of the Dispersion” (1 Peter 1:1). Christians are chosen by God to live as exiles in another country—resident aliens. The citizenship of the Christian is in heaven, but the residence of the Christian is in his city. The allegiance of God’s people is to the King of the Kingdom of God, Jesus Christ. But God’s people must love their city and their neighbors all the same. Keller notes:

Resident aliens will always live with both praise and misunderstanding. Jesus taught that Christians’ “good deeds” are to be visible to the pagans (Matt. 5:16), but he also warns his followers to expect misunderstanding and persecution (v. 10) ... Both Peter and Jesus indicate that these “good deeds” ... will lead at least some pagans to glorify God ... The church must also multiply and increase in the pagan city as God’s new humanity, but this happens especially through evangelism and discipling. (Keller, Center Church, 148.)

5 Practices of a Christian Patriot

It's not wrong to love your country, because you and I are commanded to love our neighbor. We shouldn't love it blindly, nor should we hate it blindly. Instead, consider these five practices of a Christian patriot:

- Pray for America - The Scriptures command it. Pray for your leaders, your neighbors, and your city.

- Learn the Christian Foundation Story - I know it's not a perfect place, but it's got some good stuff in the foundations. For a refresher, I recommend this book.

- Vote Well - People have bled and died so you could participate in government. Quit complaining and use your vote with wisdom and the fear of the Lord.

- Be Prophetic - Love calls out injustice. When we Christians see what is not good in our country, we should say something about it.

- Make Disciples - Evangelism in our pluralistic society is hard, but it's right. The onus is on us to show how the gospel fares in the market place of ideas that is America.

This patriotic weekend, let us remember our call to love our country — to love it well enough to tell it the truth, and to love it well enough to love Jesus more.

3 Trust Issues We All Have

Trust is a sticky issue for most of us. In bygone days, we weren't constantly bombarded with story after story of human untrustworthiness. But today our feeds are filled with clickbait-laden stories of how everyone is really quite untrustworthy. Small wonder, then, that when it comes to trusting God or anyone else, we struggle. Romans 1:17 says, "The righteous shall live by faith." But that greek word "faith" can be just as easily translated as "trust." And when I switch the words, suddenly I see all the ways that I don't trust. Suddenly I'm aware of my trust issues. Here are three I think we all have, and we all can get past with Jesus.

"I Can't Trust God."

This is the big one. When you and I hear that the righteous shall live by faith, we probably think, "Oh, I'm a man of faith. I have faith in God." But when we replace the word faith with its close synonym "trust," then the verse becomes a whole lot more difficult. Trust is active, present, and continuous. Trust is relational. Trust means, "Hey God, I trust you."

When hard times come, we feel that is somehow evidence that God is untrustworthy. "If God were good," we say to ourselves, "then He wouldn't allow this." Or maybe you do this as you read the Scriptures. Coming upon a hard passage you balk, "No God who says this could be trusted," so you walk away.

"I Can't Trust Them."

Our trust issues with God extend to people. If I had a dollar for every person who walked through the doors of my church who said, "Oh I love God, I just don't trust the church. Organized religion, man, it's where all the problems are," then I would have many dollars! Church hurt breeds a lot of mistrust. Perceived church hurt probably breeds more.

Here's the thing — trusting God inseparably entails trusting people. Why? Well because God became a person. Then, he put his Spirit in many other persons. Those people are called Christians. Refusing to trust others (especially other Christians) is a sign of a trust issue, not of a deft personal relationship policy.

"I Cant' Trust Him/Her."

Trust issues with God and with the group of God's people always trickles down to trust issues with an individual. And when we refuse to trust individuals for whatever reason we cannot carry on any kind of relationship with them. This is tragic for a million reasons, but perhaps the most tragic among them is because our mistrust of them means we can't properly love God.

You see, the Scriptures tell us that loving God means trusting people. That's what 1 Cor. 13 means when it says, "Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, eendures all things." Did you see our word? Belief. Or, you guessed it — trust. To love someone means to extend trust toward them, even if it is hard for us to do. To maintain a posture of cynical unbelief toward someone is to, in some way, be unable to love them.

Getting Past My Trust Issue

So what's a cynic like me to do? Back to the Bible. Back in Romans 1 we read that in the gospel, the righteousness of God is revealed, and the whole thing begins and ends in faith. Or, to use our word of the day, trust.

The gospel — the story of what God has done in Jesus Christ — is the ultimate proof that God is worthy of our trust. That's why Paul says that the whole kettle of fish starts and ends with trust (v. 16). To get past my trust issues, I've got to start by realizing that God has gone to an infinitely great length to prove his trustworthiness to me. Not because he had too. God doesn't have to do much. But because he loved me enough to want to. Getting past my trust issues starts with getting stuck into the story of the gospel, and letting my cynicism melt.

I'd invite you to join me. That is, if you can trust me.

How to Read a Difficult Text

This past Sunday I preached 1 Peter 3:1-8. It's not an easy text to hear for modern, Western peoples. In fact, if you read it quickly, it sounds like the first line of evidence in the argument for the case that the Bible is really just an outdated, mostly useless book. Most of us read the Bible about like we read our Facebook feed — quickly, shallowly, and on the hunt for cheap click-bait. So, when we come to a text like the one above, we're instinctively hunting for the frowny-face button to show our dislike. Let me suggest a different way.

How NOT to Read a Difficult Text

- Sweep Everything Under the "Culture" Rug

One of the quickest ways we Christians have found to alleviate ourselves from the need to listen to (much less obey) hard texts is by saying something like, "Oh, that was cultural. They believed/acted/understood that in a certain way back then, but we're in a different (which we often mean as a euphemism for "better") culture now."

Phew, that was close. For a second there, I thought we'd have to actually exegete the text. But now that you've pointed out the heretofore ignored fact that modern American society is not the same as ancient Roman society, I feel much better. #Sarcasm

No. In fact, embracing this technique is really the first step in unraveling your trust in the text entirely, because pretty soon you're the one picking and choosing what is a best fit in our culture. That's not biblical faithfulness, it's syncretism. Furthermore, it's strikingly similar to the method of Bible reading that slavery-endorsing "pastors" used in the south hundreds of years ago, and Nazi-endorsing "pastors" used decades ago. Anyone excited about the culture-driven Bible reading plan anymore? Ok, let's move on.

- React and Run Away Reactivity is almost never good, and that's especially true with the text of the Bible. When the Bible offends you, don't run away. You probably should do the when anyone offends you. Yet, we're nursing a kind of millennial angst against offense. Hurting someone's feelings is now morally equivalent to punching them in the face repeatedly. It's just that nothing about that is true. God hurts our feelings with truth so that he can show us grace. When you're offended, lean in.

How TO Read a Difficult Text

I'm taking some of Tim Keller's best ideas on this and expanding them with my own thoughts. So, let's see what we should do with a hard text when it comes and offends us.

- Consider the possibility that it doesn't mean what you think. Most of the time that we're offended at a text it's because we've read it at the aforementioned Facebook-feed-level of depth. We're just ignorant of what it's saying because we're not ancient Greek-speaking Romans (in the case of the NT audience). That why people like me go to graduate school — to understand the text so that we can explain it more accurately to our readers and listeners. So, when a text is hard to hear, ask yourself if you're hearing it rightly.

- Consider your unchecked belief in the superiority of your own cultural moment.

"That text is offensive," we say. "It's anti-woman, or anti-gay, or anti-progressive cultural values." But let's do a little thought experiment. Suppose we all got on a plane and went to Moscow, then Ramadi, and then Hong Kong. Suppose we brought our offensive Bible text with us. In each of those cities (and cultures) they would have problems with the Bible — just not your problems with the Bible. All the texts we think are regressive for women seem to progressive in Ramadi, for example. So why do you and your culture's problems with the Bible get to be the controlling, most important problems with the Bible?

Dismissing the Bible because you think it's regressive is, at bottom, an act of pretty extreme arrogance. Sitting atop your mountain of presumed progress, you look down your nose at those poor regressive (which is the NewSpeak pejorative du jour) peoples. Humility would, in this case, be listening to the text.

- Ask yourself, "Do I really want a God like me?

We all want God to be on our side, at least initially. But then we need to stop and think, do we really? I mean, you're great and all, but if God is pretty much up there agreeing with you and your culture all the time, in what sense is He God over you? At what point does God get to come and fundamentally alter or correct us and our ways of life?

In fact, relationships involve trusting the other enough to correct us. God is not a Stepford wife. He is not programmed by us for our pleasure. You can't have a relationship with someone like that. God is God, and He loves us enough to unsettle us from time to time.

- Finally, find the good news.

I love the Bible. Like, a lot. And yet there are whole chunks of it that I find really hard to read and understand. But part of the fun of reading the text is digging for diamonds. It takes hard work sometimes, but eventually you strike upon the deeper vein of treasure.

Ask yourself, "where is the good news in this text? Why would the Spirit have inspired this to be here for me to read?" Get a good study Bible, a good commentary, a good church, and get to work.

3 Meanings of the Bloody Cross

The cross of Jesus Christ is central to the Christian story. This one act — the death of the Son of God — carries with it unfathomable significance. But, like a diamond with innumerable facets, there are a few sides to the cross of Christ which are so great that it is only through them we can understand the rest. Here are three meanings of the bloody cross on that first good Friday:

Jesus Died to Absorb the Wrath of God

John Piper once wrote, “the death of Christ is the wisdom of God by which the love of God saves sinners from the wrath of God, and all the while upholds and demonstrates the righteousness of God.” [note]John Piper, Desiring God. Colorado Springs, CO: Multnomah. 1986, 60.[/note]

Here in the cross we find the resolution — the glorious, scandalous, beautiful, and terrible resolution to the tension of the entirety of redemptive history up to this point, and the sound is an awe-ful and wonderful one. Like the greatest finale to the greatest symphony ever written, Jesus’ death resolves the dissonance of our treasonous rebellion against God and God’s relentless love for us. How does it do this? How could death accomplish such a thing? Because in the death of the Son of God for sinners, God could be both just — taking sin seriously enough to do something about it — and merciful — pouring his wrath out on someone else so that he could save his people. Justice and mercy met where blood and water flowed.

Here, I think it most appropriate to let the Scriptures speak for themselves.

For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, and are justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a propitiation by his blood, to be received by faith. This was to show God’s righteousness, because in his divine forbearance he had passed over former sins. It was to show his righteousness at the present time, so that he might be just and the justifier of the one who has faith in Jesus (Romans 3:23-26).

For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God (2 Corinthians 5:21).

He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree, that we might die to sin and live to righteousness. By his wounds you have been healed (1 Peter 2:24).

Yet it was the will of the LORD to crush him; he has put him to grief; when his soul makes an offering for guilt, he shall see his offspring; he shall prolong his days; the will of the LORD shall prosper in his hand. Out of the anguish of his soul he shall see and be satisfied; by his knowledge shall the righteous one, my servant, make many to be accounted righteous, and he shall bear their iniquities (Isaiah 53:10-11).

In sin, man traded places with God. On the cross, Jesus returned the favor.

In dying for sin, Jesus did something totally unexpected — better than we’d ever dream. Jesus, quite stunningly, became our sin and shame. He took all the brokenness, all the fallenness, all the war and poverty and disease. He took the unspeakable acts of horror committed against the innocent and the unspoken acts of violence committed by the guilty. He took every foul thought, impure motive, and unholy imagination that you and I have experienced. He took every part of every brokenness, upon himself. He became sin. He became detestable. He, the beautiful Son of God, became the most disgusting of things — sin. He became all of this and, representing the sin of his people, he died. He killed sin. He destroyed death. The death of death was accomplished in the death of God the Son.

This is the atonement for sin accomplished by Jesus.

Jesus Died to Demonstrate the Love of God

This is the kind of God he is. He is not forced to save us, but out of his gracious love he does anyway. And it’s this kind of love the death of the Son of God demonstrates — the amazing love of God the Father. And, the great news about this self-sacrificing love is that anyone who would look upon the death of Jesus and believe that he died to save them, will be saved. God is not only our judge, concerned with our righteousness. He is also the father of all those who would believe, and he loves us more than we can possibly know. He has the hairs on our head numbered and all our days ordained beforehand. He knows us better than anyone else and loves us more than we can possibly imagine.

“How do you know?” you ask.

In this is love, not that we have loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the propitiation for our sins, (1 John 4:10).

That’s how we know. You can’t know how much someone loves you until you know how much their love cost them. My wife knows that I love her because of what I’ve given up. To love my wife in the covenant of marriage, I have happily relinquished my say over the rest of my life. I’ve laid aside the option of simply doing whatever I want to do. I have joyfully given up independence, the love of other women, mobility, and a host of other things to gain her as my wife. And, that was a joy for me to do. Similarly, God’s love for his people is the kind of love that willingly gives up the life of the Son of God to gain us — you and me — his people.

If God loved us with a less costly, more general kind of love, I suppose that would be nice. That kind of universal, general, we-are-the-world love may be good for a song, but it’s not good for changing a heart. To change the hard, stony heart into one that lives and beats for God requires more. That kind of love can only come from the demonstration of great sacrifice, and in this case the greatest sacrifice possible — the sacrifice of God himself. This is the kind of sacrifice which takes the deepest of offenses and the broadest of relational gaps, and crosses them — even as the Son crossed the gap of eternity to come and die for us.

Jesus Died to Reconcile Us to God and Each Other

This brings us to the third accomplishment of the death of Jesus Christ: reconciliation. In Ephesians, Paul tells us that sin separates us from God, creating an enormous chasm between us. He says:

Remember that you were at that time separated from Christ, alienated from the [God’s people] and strangers to the covenants of promise, having no hope and without God in the world. But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ, (Ephesians 2:12-13).

Our brokenness creates a void that, no matter how we may try, we cannot cross. But, the good news of the story of redemption isn’t that God sits in Heaven shouting at us, “Come over here!” For he knows that we cannot, and we would not. But God, being unimaginably merciful to us, instead says, “I’m coming there.” In coming and dying, he closes the gap and reconciles the world to himself.

Remember that the nature of our offense against God spoiled creation in at least four distinct ways. Our first and primary problem is our separation from God. But of course, being separated from God has consequences — separation from each other, brokenness within ourselves, and even the inability to rightly relate to the created world. But in the cross of Christ, God was reconciling the world to himself, and then calling us to be partners with him, heralding and demonstrating that same reconciliation that we have received. Paul tells us, “all this is from God, who through Christ reconciled us to himself and gave us the ministry of reconciliation,” (2 Cor. 5:18).

The death of the Son of God meant the end of war with God. In the sacrifice of Jesus we find the one death that ends all others, the one sacrifice that makes the two sides lay down arms and embrace in love. In it we also find the power to lay down arms against those who would be our enemies. For, if God has willingly sacrificed his son for a humanity that didn’t deserve it, then how can we, the recipients of such a sacrifice, not extend the same reconciling grace to others?

This good Friday, let us remember and reflect on the stunning love of God for sinners, and what Jesus death on a bloody cross have done for those who look on that act in faith.

5 #TrueFacts About Faith

Here are five #TrueFacts about faith:

- Faith is not a Feeling Western peoples have never fully recovered from Romanticism. We lean way to heavily on how we feel at any given moment. This is probably why so much of our church experiences these days are designed to evoke or promote certain feelings. But, faith is not a feeling. It is trust (regardless of feeling) in God.

- Faith is a Gift "For by grace you have been saved athrough faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God," (Eph 2:8). If we want to trust God more, we should ask. True we can stir the faith we have, but more faith means more asking. "Lord, I believe. Help my unbelief." (Mk 9:24).

- Faith is Powerful Jesus said that if we have faith like a mustard seed we can command mountains to move. (Matt 17:20). Whatever that means in practice, great faith brings great power.

- Faith = Trust, not Manipulation Faith means trusting God, not manipulating him. Having great faith doesn't mean you always get what you want from God. It means you always get God no matter what else you get.

- Put Faith in God, not Your Ability to Understand This is subtle, but really important. Faith says to God, "Father, your will be done." While studying the Bible introduces us to God, it does not give us secret knowledge of all His ways. Sometimes we will pray for things to which God says, "no." In those moments, we must remember that we are people of faith in God, not in our ability to comprehend Him.

What is (Not) God's Love?

God loves you. This is true, good, right, llnd beautiful. But, it's not a rug under which we can sweep all our unrepentant sin, willful disobedience, and excuse-laden, self-aggrandizing determination to do what we want. God loves us, and His love for us is different that we may think.

How God (Doesn't) Love Us

In the modern newspeak, God's love can sound like this, "God love you and accepts you just the way you are. He doesn't want to change you. He wants to surround you with His love and acceptance. So, choose love."

I wonder what you think about that sentence. Here's the thing, it's not untrue, it's just incomplete. The best lies always are. Let's pull it apart:

- "God loves you and accepts you just the way you are..."

True part: God does love his people, and accepts us into his family just the way we are. When He saved me, He wasn't merely loving the future, perfect version of Adam Mabry. He set his love on me when I was a sinner, His enemy, and an object of wrath.(Eph. 2:1-3)

Incomplete Part: God does not want to leave us the way we are. He calls us to conform us. He saves us to sanctify us. If we come to God and refuse to allow Him to change anything and everything He wishes to, we're refusing His love. (Rom. 8:29)

- "He doesn't want to change you. He wants to surround you with His love and acceptance."

True part: You and I are made in the image of God. There is some fingerprint of His divine purpose and image in all people, and no, He doesn't change that. He does wish to love us.

Incomplete Part: He does want to change you in many, many ways. He wants to give you a new heart (Ez 36:26), reorder your affections (1 Jn 5:2), change lots of your behavior (Jn 14:15), and make you become more and more like His Son Jesus and less and less like the world from which you've come. (Rom 12:2, 1 Pet 1:14) This necessarily means He will confront you in His word, rebuke you, and correct you.

Emotion and Devotion

The ooey-gooey, feckless false love the world around us offers is too low a thing for God. His love for His people is bigger and better than that.

Two words in the Old Testament shed light on the way God loves us. The first word is often translated "compassion," and is related to the Hebrew word for "womb." It is surging, maternal, emotional, and beautiful. Isaiah gives us God's words, saying, "For a tiny moment I left you, and with great compassion I will gather you." (Is 54:7). God has emotional love for his people, to be sure.

We can stop listening after that, however. Because we're such a post-Romantic, heart-driven people, that we think, "Well, if God feels emotional love toward me, He would never want to change me." So, we must keep reading.

For a tiny moment I left you, and with great compassion I will gather you. In a rush of anger I hid my face from you, but with everlasting devotion I have set myself to show you compassion. (Is 54:7-8)

The other word give to us for God's love is the word we often translate as "steadfast," "everlasting," or "devotion." In other words, God's love is His determination — His complete commitment — to fully, completely, and finally love His people.

A Bloody, Beautiful Thing

So, what does God's love look like? This:

In this the love of God was made manifest among us, that God sent his only Son into the world, so that we might live through him. In this is love, not that we have loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the propitiation for our sins. (1 Jn 4:9-10)

The very definition and highest example of love that the cosmos has ever witnessed was the moment with God's emotion and devotion collided with sin and separation on a splintered, bloody Roman cross. Two conclusion follow.

- Don't cheapen the love of God to the level of a 7th grade crush by singing songs about it, posting a Facebook meme, and then doing, thinking, and feeling whatever seems right. If God loves you with emotion and devotion then your love for God ought to involve both too.

- God changing you means God loves you, not the reverse. The opposite of love isn't hate, it's apathy. If God were apathetic toward His people — uninterested in their growth, progress, and obedience — He would not love us. He shows us this by doing for us the one thing that brings about the greatest imaginable change, dying on a cross for our sin.

Trinitarian Politics and Trending Totalitarianism

As a pastor, a Christian, and an American, I'm feeling increasingly alienated from my country's political process. I'm probably not the only one. It may not surprise you that a pastor isn't happy with politics. But what may surprise you is why. It's not because I'm a shill for the Republican or Democratic parties. Neither is my greatest alienation over a particular policy (though books could be written about policies I dislike). I'm not even most disturbed about the petulant tone of the discourse (even if it happens to resemble a middle school student election I once participated in). No, my deepest problem with our politics is a theological one.

What disturbs me, perhaps more than everything else, is the way in which our political process has abandoned the most foundational doctrine of my faith: the doctrine of the Trinity.

Trinity is a word that described the tri-unity of God. He is one God, eternally existent in three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This fact about God's nature holds endless implications, but the one most important for our current political discourse is this: If God is trinity, we matter and you matter.

Trinity Means We Matter

Christian theologians (the good ones, anyway) derive their conclusions on human interactions from the nature of God. So, if God were a radical individual (one God, one person) we may reasonably conclude that individuals may exercise supreme authority over others. But, God is not a monad (radically one). God is three-in-one. He is unity and community — a tri-untiy. That means that, for God, three matters as much as one.

Because God is Trinity, we matter — communities of individuals matter. That's not a view that started with 19th century Liberalism. It's a view that starts with God. Vintage Trinitarianism.

Trinity Means You Matter

If you were to only read the first heading, you might begin feeling the Bern. Socialism FTW, right?

Slow your roll, comrades. It's not that simple.

Because God is one God, and the individual Persons of the Trinity are in fact individual persons, individuals matter. On the Christian view, individuals should own property, do work, and exercise authority as individuals. Oneness doesn't trump three-ness. Neither does three-ness trump oneness. I matter and we matter, because the Father (and the Son, and the Spirit) matters and the Godhead matters.

Without Trinity We Trend Totalitarian

In a world of political and social brokenness, we can easily see what happens when individuals are sacrificed for the good of the community or state. We only need look as far back as World War II to find out what happens when a society decides that a certain group of individuals is undesirable. The killing fields of Cambodia, the concentration camps of Dachau and Auschwitz — these stand as monuments to the idea of the supremacy of the society at the expense of the individual. If God is simply one without internal diversity, then we would have no way to justify the rights of individuals in communities.

However today we live in an age when the rights of individuals are so over-preferred that a single person's preferences, feelings, and proclivities can change the course of the entire society, because the individual is the basic unit of society, or so it is said. If there were three separate gods, then we would have no theology to support a strong community. But, because within God there is unity and diversity, and we are made in his image, we have a means to hold in balance the rights of individuals and needs of communities. God's very nature gives us a great resource to develop a proper understanding of the balance of a civilization and its parts. Without this, what anchor have we against tyranny of the state or the citizen?

Socialism in its various forms is the idea that the "we" matters more than the "you." As I Christian, I just can't feel the Bern, I'm afraid, because Socialism is simply anti-Trinitarian. But before you righties start cheering, the Truth cuts both ways. We can't prefer individual rights at the expense of the community — Trumpian triumphalism means certain people win, while a lot of others don't. The "You" doesn't matter more than the "we."

This basic understanding was, at one point, built into the fabric of our Republic. It seems to be absent now. One party seems poised to elect a totalitarian individualist while another is tilting toward the totalitarianism of the state. Without Trinity, I'm afraid the totalitarian trend is inevitable.

What to do (and how to vote) is, well, a post for the future. But until then, vote Jesus for King.

Swinging the Hammer with Dad

My father is a general contractor. As a kid, I remember riding around with him to and from his different job sites, watching him coordinate the goings-on of the various sub-contractors. I also remember building stuff with him — decks, benches, roofs — all kinds of things. These are some of my most treasured memories. He'd correct my hammer swing, show me where to measure and cut. In all probability, I slowed him down. But, he taught me how to build. Now I've got my own home, and I've remodeled it quite extensively. I know what I'm doing because I know my dad.

I have spiritual fathers, too. And, like my dad, they build stuff. Not houses made of wood and bricks, but spiritual families made of lives and faith. They, like my dad, let me build stuff with them — churches, ministries, movements — all kinds of things.

They, like spiritual fathers, correct my hammer swing, show me how to measure my work correctly, and what to cut. In all probability, I slow them down. They have to circle back sometimes and show me the better way. But, they're teaching me how to build. Now I have my own church, and I know what I'm doing in large part because I know them.

Each generation has a choice — to build fast or to build well. Building fast is very satisfying. We make what we want, the way we want it. But because we've not explained to our sons and daughters the why and how of our structures, they find them ugly and useless. But if we give our kids — natural and spiritual — the chance to swing the hammer with us, we'll build well and they'll build with us. I'm really glad my fathers did this with me.

You Probably Didn't Know This About The Holy Spirit

On Sunday I preached on the Holy Spirit at church. Whenever the topic of the third person of the Trinity comes around, there's no shortage of misconception about His nature and His roles. Unsurprisingly, people steeped in a rigorously secular culture like ours have a difficult time embracing, much less understanding, God the Spirit. So, here are a few interesting facts about the Holy Spirit that you may not know, but should.

The Spirit Works to Advance the Mission

If you were to visit some modern Pentecostal/Charismatic churches, you might reasonably assume that the role of the Holy Spirit was to make people act oddly and occasionally fall over. In fact, the manifestations of the Spirit are, without exception, given to advance the mission of making disciples. Luke's writings make this cespecially clear. Here's a fun chart (charts are fun, btw)[note]John Hardon, "The Miracle Narratives in the Acts of the Apostles," Catholic Biblical Quarterly, 16 (1996): 303-18.[/note] explaining the miracles that Luke records in the book of Acts:

|

Miracle Associated with Peter |

Result |

Miracle Associated with Paul |

Result |

| Many signs and wonders were done by the Apostles, with Peter, among the Jews in Jerusalem (2:43) | The gospel was preached and many believed (2:47). | Many signs and wonders were done by Paul and Barnabas among the Gentiles in Asia Minor (14:3). | The gospel was preached and controversy arose (14:7). |

| Peter, in the company of John at the temple gate, heals the man lame from his mother’s womb (3:1 sq.) | Praise, and all were filled with wonder, and the gospel was preached (3:10-16). | Paul, in the company of Barnabas at Lystra, heals the man lame from his birth (14:7 sq.) | The gospel was preached and many disciples were made (14:21). |

| Peter rebukes Ananias and Saphira, who are struck dead for tempting the Spirit of the Lord (5:1 sq.) | Fear came upon the church, more believers were added (5:11, 14). | Paul rebukes the sorcerer Elymas, who is suddenly blinded for making crooked the straight ways of the Lord (13:8 sq.) | The proconsul believed the gospel (13:12). |

| The building in Jerusalem is shaken, where Peter and the disciples were praying for strength from God (4:31) | Generosity, grace, and growth resulted (4:32-37). | The prison building at Philippi is shaken, where Paul and Silas were praying and singing the praises of God (16:25 sq.) | The jailer and his whole household believe (16:31). |

| Peter is so filled with the power of God that even his shadow is enough to heal the sick on whom it falls (5:15) | More believers were added (5:14). | Paul is so effective in working miracles that even handkerchiefs and aprons were carried from his body to the sick and the diseases left them (19:12) | People repented and the word of the Lord increased (19:20). |

| At Lydda, Peter suddenly heals the paralytic Aeneas, who had been bedridden for eight years (9:33 sq.) | The residents of Lydda and Sharon returned to the Lord (9:35). | On Malta, Paul suddenly cures the father of his host, Publius, of fever and dysentery (28:7 sq.) | Provision for the mission of God was given (28:9-10). |

| At Joppa, Peter restores to life the woman Tabitha, who had been devoted to works of charity (9:36 sq.) | Many believed (9:42). | At Troas, Paul restores to life the young man Eutychus, who fell down from the third story (20:9 sq.) | The disciples were comforted and the church meeting continued (20:10-11). |

| Peter’s chains are removed, and he is delivered from prison in Jerusalem by means of an angel (12:5 sq.) | Peter was free to preach the gospel (12:19). | Paul’s chains are suddenly loosed in the prison at Philippi (16:25 sq.) | The jailer is converted (16:30). |

The work of the Spirit is to advance the mission of making disciples and glorifying God. Always, only, ever.

The Spirit Didn't Stop When The Bible Did

A common rejoinder from modern secular people is that when the cannon of Scripture was closed, the Spirit packed up all the party supplies (supernatural gifts and acts) and went home. The only problem with that is history. And the Bible.

In fact, the supernatural power of the Holy Spirit is uniformly attested to by the earliest post-biblical sources as not only normative, but critical to the mission. Early church leaders were pretty much expected to operate in the gifts of the Spirit.[note]Ronald Kydd notes that “[All the leaders] were expected to minister charismatically. . .; Ronald A. N. Kydd, Charismatic Gifts in the Early Church, (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1984), 10.[/note] The are entire books on this subject, but here are a few choice quotes:

God imparts spiritual gifts from the grace of His Spirit's power to those who believe in Him according as He deems each man worthy thereof. I have already said, and do again say, that it had been prophesied that this would be done by Him after His ascension to heaven. . . . Now it is possible to see among us women and men who possess gifts of the Spirit of God.[note]Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, 6.1.[/note]

In like manner we do also hear many brethren in the church who possess prophetic gifts, and who through the Spirit speak all kinds of languages, and bring to light for the general benefit the hidden things of men and declare the mysteries of God.[note]Iranaeus, Against Heresies, 32.3.[/note]

Others still heal the sick by laying their hands upon them, and they are made whole. Yea, moreover, as I have said, the dead even have been raised up, and remained among us for many years.[note]Iranaeus, Against Heresies, 2.32.[/note]

The history of the early church is not all doctrines and councils. Its the story of the work of the Spirit to grow the church in the midst of a hard culture.

The Spirit Is Alive and Well Today

The fastest growing religious movement in the history of the human race is the the global Pentecostal/Charismatic movement.[note]Allan Anderson, "Global Pentecostalism," A Paper presented at the Wheaton Theology Conference, 3 April 2015, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL.[/note] In fact, the story of the global church is one that is no longer shy of the supernatural, because it doesn't share Western, post-enlightenment epistemological baggage. In his book The Next Christendom, Philip Jenkins writes, “Making all allowances for generalization, then, global South Christians retain a strong supernatural orientation. . . . For the foreseeable future, though, the dominant theological tone of emerging world Christianity is traditionalist, orthodox, and supernatural.”[note]For more on this see: Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (Oxford, 2011)[/note] I love academic theology, and I love the exchange of ideas. But if we are to be academically honest, then we must admit that the engine which drives the forward progress of the gospel is not the power of the mind, but the power of the Spirit. He is alive and well and working wonders, and we need more of His power. I'll let Dr. David Martin Lloyd-Jones say it best:

In the New Testament and, indeed, in the whole of the Bible, we are taught that the baptism with the Spirit is attended by certain gifts. Joel in his prophecy, quoted by Peter on the day of Pentecost, foretells this. . . . Joel, and the other prophets who also spoke of it, indicated that in the age which was to come, and which came with the Lord Jesus Christ and the baptism of the Spirit on the day of Pentecost, there should be some unusual authentication of the message. . . . My friends, this is to me one of the most urgent matters at this hour. With the church as she is and the world as it is, the greatest need today is the power of God through his Spirit in the church that we may testify not only to the power of the Spirit, but to the glory and praise of the one and only Saviour, Jesus Christ our Lord, Son of God, Son of Man.[note]David Martyn Lloyd-Jones, The Sovereign Spirit (Wheaton, IL: Harold Shaw, 1985), 26, 33.[/note]

Never Enough

Sundays are a 17+ hour day for me, and I love them. But, every Sunday, without exception, I arrive home and feel like I should have done more. Awaiting my arrival home are usually emails from folks who thought I didn't/wasn't x enough. Accompanying them are other emails from other folks who thought I did/was x too much.

I have conversations and I wonder, "Did I say/do x enough?" I study and prepare wondering if I read and prayed enough. I lead wondering if I led well enough.

Fact: I will never be enough, study enough, care enough, or lead enough for other people.

And then I think about Jesus. Suspended on the cross by rusty nails that executed the Father's will, he said, "It is finished." He was so secure in His work and His words that He exhaled and His Spirit left His body. He stopped. He was enough.

In my not-enough-ness, Jesus is enough. In your not-enough-ness, Jesus is enough. The clamoring critics, the angry boss, the demanding children — you're not going to be enough for them. If you let them, they'll create a black hole in your soul that can never be filled. If you (and I ) lean on Jesus' enough-ness, we can help those who need our help, and when we've done enough, we can be finished. Like Jesus.

How (Not) to Know God

I occupy a weird space in church world. One foot is firmly planted in the historic, Reformed world. This is a world of exquisite theology, great exegesis, brilliant theologians, and more good doctrine than you can shake a stick at.

The other foot is firmly planted in the powerful, charismatic world. This is the world of signs, wonders, and miracles, plus the occasional oddity, as Spiritual fire is released at the cutting edge of the Kingdom of God.

My weird space — somewhere in but out of both these worlds — makes it awkward for me at theological cocktail parties (which don't really exist, but as I'm writing this, they sound like a great idea...). But I love my weird space, because the tension of these two worlds keeps me on the narrow road of knowing God.

One way not to know God is to drift into the extreme of my first foot — that of academic theology — which offers knowledge of God mostly on the basis of doctrines. Is doctrine therefore bad? Obviously not. Knowing great doctrines about God is akin to knowing great facts about your spouse. But in my experience I observe many of my fellow thinkers fall so madly in love with the doctrines that love for God is sublimated. Knowing God is about more than knowing truth about God, just like knowing my wife is about more than memorizing fact about her.

Another way not to know God is to overcorrect from the previous extreme into the other — the extreme of experiential knowledge. This extreme offers knowledge of God on the basis of an experience with him, usually at the exclusion of rigorous study, thought, or examination of the Scripture. It's the Christian equivalent of "if it feels good, it must be right." Because obviously all good vibes are from the Holy Spirit. Right? Knowing God is about more than having experiences with Him, just like knowing my wife is about more than having experiences with her.

It seems to me that knowledge about God and experience with God fuel our pursuit of God. Let's go back to my weird space.

I love thinking hard about God. The intellectual rigor of theology is fun to me. But as soon as I feel myself ascending the high tower of knowledge which excludes me from my less theologically inclined brethren, the Holy Spirit pulls me to Himself in experience. Some prayer, worship, or moment with God calls me out of the library and onto the mission. But, on the field of battle, I realize that I need more than faith and fire. I need to understand God more deeply. So my experience drives me back to the text. And I can't stay in the text long before I am compelled from the text into the world. And on the cycle goes.

The narrow road of knowing God features knowledge and experience — life and doctrine. So get out there and learn something about Him you didn't know. Then, like fresh logs on a fire, let your knowledge fuel your worship and work for the God you're knowing better.

Revelation v. Speculation

How can we know God? This question comes up when I teach Life and Doctrine more than any other. We, having been brought up under the tutelage of a thorough-going secularism, want a sort of logical, mathematical proof of God's existence. They're asking, "How can I get from where I am up to truth about God?" The truth is that this question is almost completely backwards.

Luckily, we're not the first humans in history to think about this. About 500 years ago the writers of the Belgic Confession stated:

[We know God] first, by the creation, preservation, and government of the universe, since that universe is before our eyes like a beautiful book in which all creatures, great and small, are as letters to make us ponder the invisible things of God... Second, he makes himself known to us more openly by his holy and divine Word... [note] The Belgic Confession, Article 2. [/note]

Knowing God starts when we shed the Scientistic vision of the world and embrace a revelational view. It's not that Christians should dislike science. It's that we cannot believe that science is the best way to know all things. The Belgic Confession reminds us that God has given us the world and His Word not as clues, but as books. We're not trapped in a cosmic version of Law and Order, piecing together the clues of a God in hiding. The Christian must flip that script. God is speaking to us through these two books—through revelation.

Here are a few reasons this matters:

Revelation Changes the Questions We Ask

Because we understand the world is made by God, we understand that the world and the Word both speak to us about God. Therefore, the question we ask goes from "Where is God," to "What does x say about God?"

Revelation Begets Humility, Scientism Begets Pride

If the world is designed to speak to us about God, then we know Him because He revealed Himself. If Scientistic speculation is the greatest epistemological framework, then knowledge of God (or anything else) is obtained because we were smart enough to look for it.

Revelation Explains Science

Dr. John Lennox, in a debate with infamous atheist, Richard Dawkins, attempted to explain this to his opponent by saying, "You've got to believe in the rational intelligibility of the universe before you can do any science at all. Science doesn't give you that." [note]John Lennox. The God Delusion Debate, hosted by Fixed Point Foundation. Birmingham, AL, 2006.[/note] One has to believe that the universe is orderly, fixed, and law-like for science to get moving in the first place — a belief that was supplied buy the worldview of Christian revelation, creating the conditions necessary for the scientific revolution to happen at all.

Paul Davies, theoretical physicist and one of the most influential expositors of modern science agrees, saying:

Science is based on the assumption [on faith!] that the universe is thoroughly rational and logical at all levels... Atheists claim that the laws [of nature] exist reasonlessly and that the universe is ultimately absurd. As a scientist, I find this hard to accept. There must be an unchanging rational ground in which the logical, orderly nature of the universe is rooted.[note]Paul Davies, "What Happened Before the Big Bang?” in God for the 21st Century, ed. Russell Stannard (Philadelphia: Templeton Foundation Press, 2000), 12.[/note]

Here's the big take home: God isn't playing a game of cosmic keep-away. God is very interested in revealing Himself to us. The only question is whether or not we'll receive the knowledge the world and the Word give us as genuine knowledge, or just speculation.

4 Moral Responsibilities We All Have To Truth

There is an interesting reaction happening among many young Christians. It is the cautious conviction that it is, perhaps, wrong to speak truth. Friedrich Nietzsche claimed that deep within us all lies der wille zür macht (the will to power). This is the idea that each of us are consumed with gaining power and prominence over others. According to Nietzsche, this goes for (especially) us religious folks. Some of us are pretty convinced that when someone says they "know God," they're acting immorally, irresponsibly, or even dangerously. Postmodern philosopher Denis Diderot famously said, "Men will never be free until that last king is strangled on the entrails of the last priest."(1) Yikes.

But, the fact remains that some people use their claim to know truth as a wedge for power.

This may surprise you, but this objection wasn't first sounded by hippie philosophy students who were trying to throw off the oppressive shackles of "the Man." It was sounded by Jesus. This was the same accusation that Jesus leveled against the Pharisees. He said of them, "[They] tie up heavy burdens, hard to bear, and lay them on peoples' shoulders, but they themselves are not willing to move them with their finger."(Matt. 23: 4). Did Jesus just agree with a postmodern critique of religion? Why yes he did.(2)

Yes, truth can be misused. And yes, truth can go unsaid. But these observations are hardly new. Jesus criticized the religious leaders of his day over the same sorts of things. Why? Because truth is all tangled up with moral responsibility, and we all already know that. We sue people for false advertising. Lying politicians (hopefully) get voted out. When a spouses lie, divorce may follow. We all know that we have a moral connection to truth. Here are four ways that plays out:

To Know It

The biggest problem with humanity is that we, in sin, suppress the truth in unrighteousness (Rom 1:18). According to the Scriptures, truth became flesh in Jesus. And according to those same Scriptures, knowing Jesus sets us free from sin's lies. There's nothing morally praiseworthy about believing what is false.

To Believe It

When we know truth, we're then accountable to believe it. You can sell books with clever sounding unbelief, but that's just the adult version of that annoying, know-it-all friend from third grade. Everyone knew he was full of hot air then, and he still is, even though he sells books. If truth is true, then we are accountable to trust it.

To Teach It

Truth is to be shared. Just as it would be unjust to knowingly teach school children incorrect mathematics, it is unjust to knowingly perpetuate falsehood. Why? Because lies don't lead to human flourishing. If incorrect equations make technology work incorrectly, then incorrect moral and metaphysical beliefs will have the same effect on the soul. We have a moral responsibility to not obfuscate, but to educate — to speak clearly and not deceptively.

To Not Misuse It

The reason so many are so scared to speak truth clearly is because we've seen it misused. We've seen truth said unlovingly, and it hurts. We've watched people who thought they knew truth hurt folks who were "wrong." Our reaction, however, has been to toss the baby out with the bathwater. One moral failure (not speaking truth) doesn't fix another (misusing truth). We must be among those who use truth truthfully.

The good news is, we've got really good precedent for faithful, useful truth telling. Jesus Christ is truth made flesh (John 14:6). He knew it, even though everyone around him wanted to deny it. He believed it, even through it was thoroughly unpopular. He preached it, because he knew that only through contact with truth can humanity be rescued from the lie of sin. And he never misused it, but came under the penalty of those who did, to rescue them.

Let's stand up in fidelity to truth. After all, truth has already done so for us.

(1) Denis Diderot, attributed by Jean-François de La Harpe in Cours de Littérature Ancienne et Moderne (1840)

Social Justice Needs Personal Righteousness

"Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly." - Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Letter from a Birmingham Jail

We live in the day and age of the social justice warrior — the young man or woman committed the ideas of making the world "out there" more just. Conveniently, you can qualify for this job without any concern for your personal righteousness — a grave injustice itself. But, since today is MLK day, I feel it's important to remember that King (and Paul, and Jesus, and all the prophets) didn't share this rather modern (rather ridiculous) view.

When Dr. King wrote his now famous Letter from a Birmingham Jail, it included the oft-repeated phrase, "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere." And, that's true. But before you ride your noble steed off into the unjust world to "fix it," it would be helpful to remember the rest of the idea. "We are caught in an escapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly."

In other words, it's not just morals "out there" that matter — what we often call social justice. It's also our personal righteousness "in here" that counts — what we call morality. If we're really serious about pushing back racism, sexism, classism, and the many other ills from which our culture suffers, we must also be serious about personal righteousness. They are all connected — we are all connected. If I'm struggling morally, somehow that will affect society. Conversely, if society is riddled with injustice it will affect me. It sounds counterintuitive to us, but it's true.

Scripture declares that righteousness and justice are the foundation of God's throne. That explains why God connected the ideas in Jesus' great commandment — to love God and other people. Because, they are connected.

All this means that I'm personally very grateful for Dr. King. His struggle for justice is connected to even my personal righteousness. I can't be who I'm called to be without his efforts to make the world better. In response, let's commit to grow more personally righteous through Christ. Only then will this work look more like Heaven. As righteousness and justice meet in our lives, they'll meet in our world.

"Is" Can't Make "Ought"

For a long time, philosophers have made the case for God's existence based upon a moral argument. Rationally-minded atheists have countered by saying that one can be good without believing in God. And that's true — one can act in a way that most of us find morally praiseworthy without believe in God. You just can't explain why.

Here's the point: the rational sciences are quite good at making "is" statements. Light is both a particle and a wave. Water is two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen. Eating a pound of bacon a day is bad for your health (but really delicious).

But rationality alone can't take you from "is" to "ought." Just because we can scientifically demonstrate that eating the aforementioned daily pound of bacon will have deleterious effects on your heath doesn't mean you ought not do it. In order to believe you ought not do that you must first have some pretty strong beliefs (on faith) about human nature, its value, and that living a long time is more morally praiseworthy than choosing to die and early death for the love of pork products. In other words, you need more than mere rationality.

Alvin Plantinga warns us against placing all our epistemological eggs in the basket of the rational sciences, saying:

Some treat science as if it were a sort of infallible oracle ... Many look to scientists for guidance on matters outside of science, matters on which scientists have no special expertise. They apparently think of scientists as the new priestly class; unsurprisingly, scientists don't ordinarily discourage this tendency. (1)

Before your take all your oughts from the "sciences," do a little thought experiment with me ... if you're brave enough to be unsettled. Ask yourself, what are those "ought" statements that you believe so strongly? Now ask yourself what beliefs you have to believe to believe so strongly in those statements?

Where do those strong beliefs come from?

At the end of that chain of reasoning, you might find yourself standing next to God. Which isn't a bad place to start figuring out the "oughts" of life.

(1) Alvin Plantinga, Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, Religion, and Naturalism (Oxford, 2011) 18.

Dangerous Doubt and Why You Need It

Let's talk about doubt. For some, doubt is a big bogeyman. Feel doubts about your faith? Expunge them with all haste!

Well, maybe.

I depends on the kind of doubting you're doing. But you may be surprised by what the Scriptures actually say about doubt.

You're Commanded to Doubt

You may not know this, but the Bible actually commands Christian to doubt. At least, a kind of doubt. Paul wrote, "Test everything, but hold fast to the good." (1 Thes. 5:21) This the wise, soul-protective doubt that keeps faith filled disciples from becoming foolish chumps who believe anything that looks vaguely Christian. Understood in this way, I can't help but think that a whole lot fewer end-times books would sell if Christians took Paul's command to heart.

When Doubt is Dangerous

Doubt is dangerous when it metastasizes into the cancer of cynicism. Cynicism is a false epistemology — a way of knowing that says, "You can't know that," about everything. It takes the position that truth can't be found. But saying "I don't believe that," about everything is just another way of saying "nothing is to be believed," about anything. C.S. Lewis exposes the foolishness of cynicism when in The Abolition of Man,

You cannot go on 'seeing through' things forever. The whole point of seeing through things is to see something through it. It is good that the window should be transparent, because the street or garden beyond is opaque. How if you saw through the garden too. It is no use trying to 'see through' first principles. If you see through everything, then everything is transparent. But a wholly transparent world is an invisible world. To 'see through' all things is not to see.(1)

Look, I get cynicism. Cynics sound smart, but they're not. They're fools engaging in a sophistry that hides the fearful insecurity and lack of trust that marks hurt hearts.

Some Things You Should Never Doubt

There are some things that you should never doubt. God's character, never doubt that. God gave you his Son when you gave him the finger. That's a good God. God's love, never doubt that. His love for you and I cost him everything. There are more things not to doubt, surely. But of all people, Christians shouldn't fear doubt. We should fear the slide that doubt may place us on toward the cancer of cynicism. So, doubt well.

(1) C.S. Lewis. The Abolition of Man. Pg. 53-54.

Disagree ≠ Hate

In her biography on Voltaire, Evelyn Beatrice Hall wrote, "I disapprove of what you say, but I'll defend to the death your right to say it." For many years now her words have been the mantra for freedom of speech in Western society. And for many years, most of us have simply presumed that the right to say what’s on our mind (even if others think it to be wrong) was, indeed, right. In recent years, however, this basic foundation of American (thus, Western) society has come under pressure. As the internet has connected us more than ever, it's also divided us more than ever. Instead of connecting all of us to each other, we have preferred connections to others most like us. Instead of one shared set of values, we now hold the values of whatever subculture to which we're most inclined. This means that today there is not one American spirit, for example. Now there are a myriad of cultural nation-states which hold our allegiances far above our country. So what do we do when those values come into conflict?

Formerly, we would argue vigorously. Our shared set of values meant that, ideally, we would listen, presume the best intentions of our opponents, and seek to find some kind of working consensus. But today such work is rare. Why? Because we have come to believe that to disagree with someone is equivalent to hating them.

That is a lie.

Here are the basic ideas I'd like to make clear:

- To disagree with someone is not to hate them.

- Love disagrees, often very passionately, with the beloved.

- Freedom of speech exists in direct proportion to love.

- Therefore, the action of disagreement should be an action of love.

First, we must rid ourselves of this idea that disagreement is hatred. That's just obviously silly and false. I disagree with my wife quite a lot and I love her more than anyone else on this planet. Is she to take my disagreement as a sign of hatred? Certainly not. Further, I pastor a church filled with people with whom I disagree about a ton of things: politics, ethics, the superiority of mac to pc ... the list goes on. Do I hate them? Good grief, no. I'm their pastor for goodness sake. If I hate someone (and I shouldn't, but if I did) I would probably disagree with them, but the reverse is not true. If I disagree with someone, I do not therefore hate them. Thus, (1).

In fact, the opposite is quite true. If I am passionate in my disagreement with you, it is more likely to be a sign of my love for you. Again, take my wife, for example. I love her. I've made a life-long covenant with her. So if I disagree with her about, say, how to parent one of our children, or where we should live, or how we should spend our money, I don't hate her. I love her, and am so committed to her welfare that I want her to get it right. And she wants me to get it right, so she pushes back. In fact, I want to get it right, right along with her. I want agreement on the good, and that may involve the passionate exchange of ideas (a euphemism for arguing). Therefore, premise (2).

Let's expand the analogy to society. We're supposed to live in a culture where the marketplace of ideas weeds out the good ideas from the bad ones through debate, honest disagreement, and passionate dialogue. But what makes such a marketplace possible? Love. Without a deep love for the image of God in you, I won't care to passionately debate you. I'll just want to silence you. But far from being a sign of hatred, vigorous, careful disagreement is a great sign of love and respect. Hatred silences, love discusses (even at painstaking length). Hatred freaks out when challenged. Love sees a challenge as an opportunity to refine one's position and win the other to it. Without love there is no real freedom — to speak, or to do anything else for that matter. Thus, (3).

These basic (and sadly no longer obvious) premises bring us to (4) — disagreement should be an action of love. As a Christian who holds to more or less really old beliefs about God, Jesus Christ, the Bible, money, sex, humanity, etc., there is a lot to disagree with these days. So when I write, speak, and argue for the veracity of these ideas I'm often called a hater. Have I been hateful before? Probably, but my point here is that I shouldn't be. We shouldn't be.

Think of it this way: If I find a truth that others don't believe, the most hateful thing I can do isn't to argue with them, but to leave them in their error. If they really are in error then their error will probably not bring about their ultimate good. But in withholding that fact I haven't loved them, affirmed them, or tolerated them. I've hated them. I've preferred myself, my comfort, my good name, and my ease of life to their good, their joy, and their prosperity. The opposite of love turns out to be selfish apathy toward others.

Furthermore, if disagreement is hate, then Jesus Christ is the most hateful being to have ever lived. Why? Because he came in complete disagreement with every human, of every culture, at the core of their belief structures. His hate speech included calling everyone wrong (Mark 12:27), telling them that they are following the father of lies (John 8), and correcting the wrong moral behavior of all of us (John 3, 4, Matt 5, et. al.) He was such a hater that the progressive, tolerant, and culturally savvy Romans decided to execute him. And what did he say as he bled? "Father forgive them, they don't know what they are doing." Even with his dying breaths, he begged our forgiveness on the basis of our error and ignorance.

That's because he loves us. This man who disagreed with the whole world did so not from hate but from love. In fact, so great was his love for humanity that he willingly embraced death both to show us the error of our ways and open the way for us to live in accordance with the truth.

Shall we be a people who really love one another enough to painstakingly, passionately, and carefully argue for truth? Or, shall our hatred for one another run over the banks of our better natures, silencing, shouting, and insisting that to disagree with you is the same as hating you? Apparently, I love you enough to ask you.